Ever wonder why you can’t stop checking your phone or find yourself mindlessly snacking when you’re not even hungry? The line between habit and addiction can be blurry, but understanding the difference is crucial to gaining control over your behavior.

Are your habits slowly turning into an addiction?

Habits and addictions are shaped by a complex interplay of biological, psychological, and environmental factors. Here are some key data and statistics:

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, an estimated 130 people die every day in the United States from drug overdoses. Drug addiction affects millions of Americans across all demographics.

- Research has found that people who are genetically predisposed to seeking out novel experiences and sensations are at higher risk for developing addictions. However, genes are not destiny, and the environment plays a large role.

- Habits are formed through neural pathways in the brain that strengthen with repetition. It takes an average of 66 days for a new habit to form, but habits can be broken with focused effort and replacement with new routines.

- Addictions involve changes in the brain’s reward system that go beyond habitual behaviors. Addicted individuals often experience intense cravings and a loss of control over their behaviors.

- About 9% of Americans over age 12, struggle with a substance use disorder, while only 0.2% to 0.3% have a gambling disorder, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse. However, many people exhibit addictive behaviors related to things like social media, video games, sex, food, and more.

In this article, we’ll explore habits and addictions in depth to help you determine if you’re exhibiting a harmless habit or need to make a change due to an addiction.

Get ready to learn all about the psychology and science behind what drives your daily actions, pick up useful strategies for building better habits, and find the motivation and tools you need to overcome addictive tendencies for good. Whether you’re simply curious or seriously concerned about yourself or someone you care about, this guide will provide the answers and advice you’ve been looking for.

Defining Habit vs Addiction

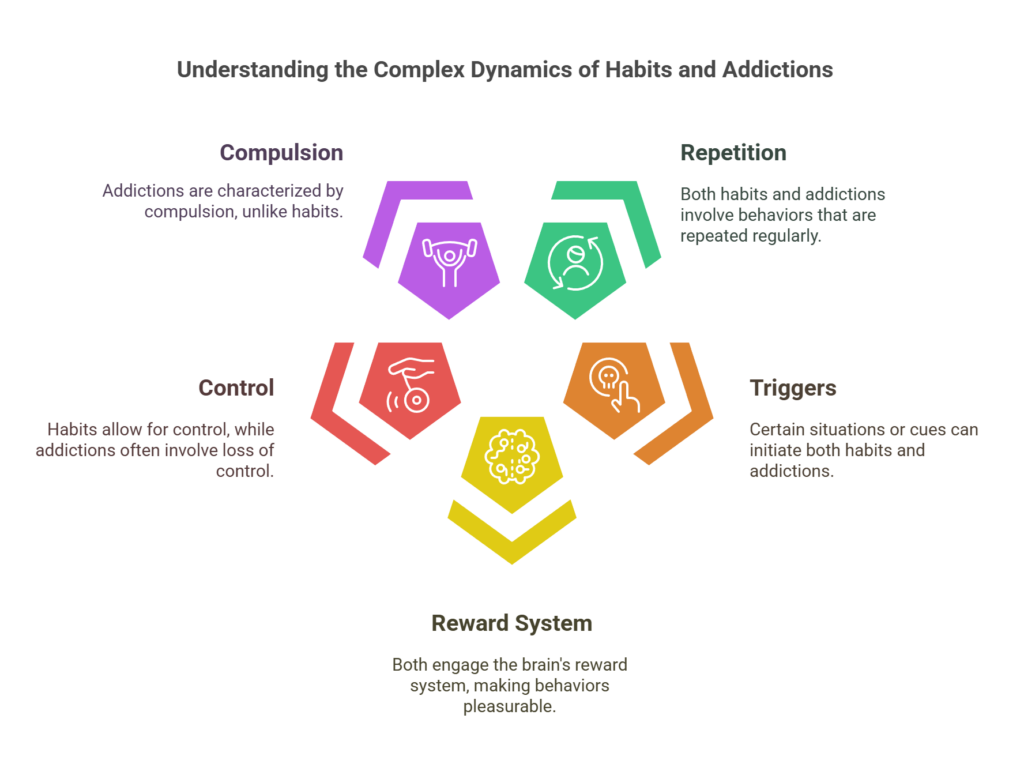

A habit is a routine behavior that becomes automatic over time, while an addiction is a compulsive behavior that is difficult to control. Although habits and addictions share some similarities, there are a few key differences to understand.

1. Loss of Control

The main distinction between a habit and an addiction is loss of control. With a habit, you remain in control of your actions and can choose to stop the behavior if needed. An addiction, on the other hand, involves a craving that becomes uncontrollable, often continuing the behavior even when there are negative consequences.

2. Impact on Daily Life

Another sign of addiction is if the behavior begins to interfere with work or relationships. Habits typically do not cause issues with day-to-day functioning, whereas an addiction can become the main focus of someone’s life and compromise responsibilities.

3. Difficulty Quitting

It is relatively easy to break a habit through conscious effort and willpower. An addiction is much harder to quit, often requiring professional help or a customized treatment program. The urge to relapse into addictive behaviors tends to be very strong.

4. Underlying Cause

Habits develop from repetition and reinforcement over time, serving a utilitarian purpose. Addictions tend to be linked to an underlying issue, such as anxiety, depression, trauma, or low self-esteem. The addictive behavior acts as an escape or way to cope with negative emotions or or events.

The good news is there are strategies for overcoming addictions and replacing unhealthy habits with positive ones. Understanding the difference is the first step toward making lasting changes and living a balanced life. With support, commitment, recover from addiction. and the right resources, people can and do recover from addiction.

The Psychology Behind Habit Formation

Habits form gradually, through a process of reinforcement and reward. As we repeat behavior and experience positive outcomes, neurological pathways in our brain strengthen, making that behavior automatic.

Once a habit forms, we can do it without having to think about it consciously. Our habits shape a huge portion of our daily lives, from how we wake up in the morning to what we choose to eat. While good habits can benefit us, bad habits and addictions negatively impact our health, relationships, and quality of life.

The psychology of habit formation involves several key factors:

- Cue: A trigger that prompts the habit to start, like a time of day, emotional state, or place. The cue signals your brain to go into “autopilot” and perform the habitual behavior.

- Routine: The actual habit or sequence of behaviors. This can be physical, mental, or emotional. The routine is the most important part of the habit loop.

- Reward: The benefit you gain from the habit. This could be physical (like a cigarette), emotional (like comfort from a daily routine), or mental (like satisfaction from checking email). The reward further reinforces the habit loop.

- Craving: The desire and anticipation of the reward. Cravings drive habits and make them hard to break. They activate the reward centers in our brain, even before we engage in habitual behavior

Understanding how habits form is the first step to gaining control over them. By Identifying the cues and rewards that drive your habits, you can work to build healthy new routines and overcome unhealthy addictions. With practice and persistence, you can rewire your habits and transform your life for the better.

How Addictions Hijack the Brain’s Reward System

Addictive substances hijack your brain’s reward system, flooding it with dopamine and tricking it into craving the substance. Your brain remembers the rush of dopamine and associates it with the addictive drug, cementing the addiction.

Addictive drugs release dopamine, the “feel-good” neurotransmitter, in the brain’s reward pathway, the nucleus accumbens. Normally, the reward pathway releases dopamine in response to natural rewards like food, sex, and social interaction. Addictive drugs, however, can release up to 10 times more dopamine than natural rewards.

This flood of dopamine feels highly pleasurable and rewarding. Your brain remembers this dopamine surge and associates it with the addictive substance, essentially rewiring itself. The brain now links the drug with survival by remembering the dopamine rush. This fuels craving and compulsive drug-seeking behavior.

The brain’s prefrontal cortex, responsible for self-control and judgment, is weakened. The amygdala, involved in emotional regulation and stress, is strengthened. This Imbalance makes it much harder to quit using the substance. The brain has adapted to expect the drug.

Addictive drugs have a crucial addictive-drug-sensitive component in the brain’s reward circuitry. They activate a specific receptor, the dopamine D2 receptor, that is critical for addictive behavior. Blocking this receptor can help overcome addiction.

To overcome addiction, the brain must relearn natural rewards by re-strengthening connections between neurons. This difficult process takes time and conscious effort through lifestyle changes, counseling, medication, and support groups. Understanding how addiction affects your brain can help motivate you or a loved one to commit to recovery and build new neural pathways of health and wellness.

Identifying Unhealthy Habits vs Harmful Addictions

The difference between an unhealthy habit and a harmful addiction can be subtle. Here are some ways to determine if a behavior has crossed the line into addiction.

1. Loss of Control

With an addiction, you feel unable to stop or limit the behavior, even if you want to. You may make repeated attempts to quit or cut back, but ultimately fail. An unhealthy habit is something you can choose to stop, even if it’s difficult. You’re still in control.

2. Consequences Don’t Matter

When addicted, you continue the behavior even when it causes significant problems in your life. Addiction becomes more important than relationships, health, work, or financial stability. Unhealthy habits may have minor consequences, but you can weigh the pros and cons and make adjustments.

3. Physical Dependence

Addictions often involve physical dependence, meaning you need the substance or behavior to function normally. Quitting abruptly can lead to withdrawal symptoms. Habits typically do not cause withdrawal symptoms or the inability to feel normal without them.

4. Time Spent

Addictions occupy an increasingly large amount of your time and mental space. You may spend hours engaged in the behavior each day, constantly thinking about it or planning how to do it next. Unhealthy habits do not take over your schedule or dominate your thinking. You can still enjoy and focus on other life activities.

5. Secrecy

Addictions are often kept hidden from others due to feelings of guilt or shame. You may lie to cover up the depth of your addiction. Unhealthy habits, while problematic, are usually not kept a secret or a source of strong shame. You remain open about the behavior with close ones.

The path to overcoming addiction starts with recognizing the problem. Be honest with yourself about whether a behavior has become an addiction, then seek help from medical professionals. Building awareness and a strong support system are the first steps to recovery. There are always alternatives to unhealthy habits and addiction. You have the power to create positive change.

Warning Signs You May Have Crossed From Habit to Addiction

If your habit has crossed into addiction, several warning signs may become apparent. Addiction means you feel unable to stop the behavior, even when you want to or know you should. Some key signs you may have an addiction include:

1. Loss of Control

You find yourself unable to stop indulging in the habit when you intend to. For example, you plan to have just one drink but end up drinking excessively. You feel a compulsion to continue the behavior that overrides your self-control.

2. Continuing Despite Consequences

You continue the behavior even though it causes problems in your relationships, health issues, financial troubles, or other negative impacts. Yet you feel unable to quit or cut back.

3. Cravings and Preoccupation

You experience intense urges and cravings for the habit or substance. When you’re unable to engage in it, you feel restless, irritable, and discontent. The habit occupies your thoughts constantly.

4. Hiding or Lying About the Behavior

You hide the extent of your habit from others or lie about it to avoid judgment or Intervention. This secrecy and deception is a sign the habit has become unhealthy.

5. Increased Tolerance

Over time, you need more of the substance or habit to get the same effect. For example, one drink used to give you a buzz, but now it takes three or four. This tolerance indicates your body and mind have adapted to the behavior in an unhealthy way.

6. Withdrawal Symptoms

When you stop or cut back, you experience physical and psychological withdrawal symptoms like nausea, shaking, mood swings, and cravings. Withdrawal shows your body has become dependent on the habit or substance.

If several of these signs resonate with you, your habit may have progressed into addiction. The good news is there are many resources to help you overcome addiction and build healthier habits. Speaking with a medical professional is often the first step.

Building Healthy Habits: Tips and Strategies

Building healthy habits and overcoming addictions is challenging, but with the right mindset and strategies, you can succeed. Start by focusing on small changes and track your progress to stay motivated.

1. Start small and build up gradually

Don’t try to overhaul your life overnight. Pick one habit to focus on, like going for a 15-minute walk 3 times a week or drinking an extra glass of water each day. Once that habit sticks, build on your success by adding another small change. Taking incremental steps will make the process feel more achievable and help you stay consistent.

2. Find your motivation and reward yourself

Identify why you want to build this habit or break an addiction. Do it for your health, relationships, finances, or productivity. Remind yourself of your motivation regularly to maintain your determination. Also, give yourself rewards along the way to stay on track, whether it’s a nice meal out or an evening of watching your favorite show.

3. Track your progress and be accountable

Use a habit tracker, calendar, or journal to record your progress. Note how often you do your new habit or avoid addictive behavior. Seeing your progress in black and white will keep you accountable and motivated to continue improving. Tell a friend or family member about your goal so they can check in on your progress too.

4. Learn from your mistakes and try again

Don’t be too hard on yourself if you slip up. Everyone falls off the wagon sometimes. The key is to not give up completely. Acknowledge what went wrong and get back to your routine the next day. You may need to revisit your motivation or modify your approach. The more you practice, the easier it will get. Success is a journey, not a one-time achievement. Stay determined and never stop trying.

With practice and perseverance, you can retrain your habits and overcome addictions. Stay focused on your motivation, start small, track your progress, learn from mistakes, and keep trying. You’ve got this! Make each day a chance to build on your success and become your best self.

Overcoming Addiction: Treatment and Recovery Options

Once you’ve identified an addiction, the path to overcoming it typically involves treatment and a long-term recovery process. There are many options available for addiction treatment, including:

1. Inpatient Rehabilitation

Residential rehab facilities provide 24-hour care and support. Patients stay on-site while receiving intensive treatment through counseling, therapy, and medication (if needed). Inpatient rehab allows you to focus fully on your recovery in a controlled environment.

2. Outpatient Treatment

Outpatient programs provide care and treatment while allowing you to live at home.

Options include Individual or group counseling and therapy. Meet with a counselor or therapist on your own or join a support group.

Partial hospitalization or intensive outpatient treatment. Receive treatment during the day but return home at night. Useful for those transitioning from inpatient rehab to independent living.

Medication and medical care. Work with doctors or psychiatrists to manage withdrawal symptoms and health issues related to your addiction.

3. Recovery Support Groups

Groups like Narcotics Anonymous (NA) and Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) offer ongoing support through the challenges of sobriety and addiction recovery. Connecting with others struggling with similar issues can help provide motivation and accountability. Support groups are free to join and available in most communities.

The recovery process often lasts a lifetime. Making long-term lifestyle changes and learning coping strategies to avoid relapse are key. It may take trying different options to find what works for you. Don’t get discouraged if you relapse-just get back to your treatment plan and focus on your motivation for becoming and staying sober. With time and dedication, you can overcome your addiction and maintain a healthy life free from substance abuse.

Creating a Supportive Environment for Change

Creating a supportive environment is key to making positive changes in your life, whether it’s developing a new habit or overcoming an addiction. The people around you and the places you frequent can have a huge impact on your success.

Surround yourself with a strong support system of people cheering you on. Let close friends and family know about your goal so they can encourage your efforts and check in on your progress. Consider joining an online community or local group with similar goals. Having accountability partners and a team of like-minded individuals will make the journey much easier.

Similarly, spend less time in environments that enable unhealthy behaviors and more time in those that promote the changes you want to make. If certain friends or locations trigger cravings or temptations, avoid them when possible. Out of sight, out of mind.

Your environment also includes the online spaces you inhabit. Follow social media accounts and subscribe to websites that provide motivation and helpful information related to your goal. Mute or unfollow anything that glorifies addictive tendencies or distracts from what you’re trying to achieve.

Every small change you make to build a supportive environment will help ensure your success in developing better habits and freeing yourself from addiction. Surround yourself with positivity, seek out accountability, and limit exposure to triggers and temptations. With the right mindset and environment, you’ll be well on your way to lasting change.

Your Path to Recovery Begins Here

Habit vs Addiction FAQs: Your Top Questions Answered

1. What’s the difference between a habit and an addiction?

A habit is a behavior that you repeat regularly, often without thinking about it. Habits are generally harmless or even helpful. An addiction, on the other hand, is a compulsive behavior that you have little control over. Addictions negatively impact your life and health.

2. How do I know if I have an addiction?

Some signs of addiction include:

- Losing control over the behavior. You can’t stop even if you want to

- Continuing the behavior even when it causes problems.

- Craving the behavior or feeling restless or irritable without it.

- Finding that you need to increase the behavior to get the same effect. This is known as tolerance.

- Experiencing withdrawal symptoms when you stop. This could include anxiety, sweating, shaking, etc.

- Spending a lot of time engaging in the behavior or recovering from its effects.

- Giving up important activities because of the behavior.

- Continuing the behavior even when it puts you in danger.

- Lying to others to hide the extent of your behavior.

- Feeling unable to limit how much you do something.

- Needing the behavior to relieve bad feelings like stress, anxiety, or depression.

3. How do I build healthy habits and break addictions?

The keys to building good habits and overcoming addictions are:

- Awareness. Pay close attention to your triggers and behaviors. Monitor how often and why you engage in them.

- Accountability. Tell a friend or loved one about your goal and ask them to check in on your progress. Consider working with a therapist or support group.

- Replace the behavior. Find an alternative behavior to do instead of the habit or addiction. Keep your hands and mind busy.

- Reward yourself. Give yourself reinforcement and incentives for your accomplishments and milestones. Celebrate small wins along the way.

- Make a plan. Decide how you will avoid triggers and temptations ahead of time. Have strategies in place for cravings and slips. Planning and preparation are key.

- Take it day by day. Don’t feel overwhelmed by the big picture. Focus on the current day and the behaviors you want to change right now. You’ve got this! One day at a time.

- Get support. Connecting to others who share your struggles can help keep you accountable and motivated. Find online communities or local support groups.

- Be patient and compassionate. Significant change takes time. Avoid harsh self-judgment if you slip up. Learn from your mistakes and get back to your goal. You deserve to lead a happy, healthy life free from addiction.

Conclusion

Now you have a deeper understanding of the critical differences between habits and addictions. Remember that habits are healthy behaviors that you are in control of and can modify as needed to suit your needs and goals. Addictions, on the other hand, are compulsive behaviors that are out of your control and negatively impact your life.

The good news is you have the power to build positive habits and overcome addictive tendencies. Start small by choosing one habit or addiction to focus on, set a concrete and realistic goal, and track your progress. Celebrate your wins, learn from your slip-ups, and stay committed to continuous self-improvement. You’ve got this! With knowledge and determination, you can achieve a balanced and fulfilling life free from addiction. The journey may not always be easy, but it will be worth it. You owe it to yourself and your loved ones to be the healthiest and happiest person you can be. Now go out there and make it happen!